'The untold story'

Occupational illnesses pose a greater threat to workers than occupational injuries but can be more difficult to identify

It started as a persistent cough.

After years spent working odd jobs at an East Coast foundry, John Franklin* was used to the dust at his worksite. While he knew the dust might not be great for his health, he figured the cough was simply irritated sinuses.

When the cough would not go away, he went to the doctor’s office. An X-ray of his chest showed something “fuzzy,” and further tests revealed an unexpected result: John had silicosis, a deadly lung disease caused by exposure to silica dusts – the same dust he was exposed to at work. “I didn’t think it could be something this dangerous in the product that I used at work,” he said in an interview with Safety+Health.

Unfortunately for John and thousands of other U.S. workers, some products at work can be harmful enough to cause a number of occupational illnesses, including cancer.

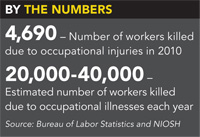

By some estimates, as many as 10 times the number of workers dies every year from occupational illnesses than from occupational injuries. Despite these staggering figures, the impact of occupational illnesses can be hard to understand and control.

“There’s really no comprehensive surveillance system to monitor worker illnesses,” said Dr. Doug Trout, a physician and associate director for science for NIOSH’s division of surveillance, hazard evaluations and field studies. “There are a lot of uncertainties.”

A numbers game

Of the 3.1 million nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses in 2010 estimated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, only about 5 percent – or 158,000 – were illnesses. But these figures leave out potentially thousands of occupational illnesses, a fact BLS acknowledges.

“We do not believe that the Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses and Census of Fatal Occupational Illnesses are the appropriate vehicles to capture latent nonfatal illnesses or deaths – like those resulting in cancer – from workplace exposures,” said Bill Wiatrowski, associate commissioner for BLS’ Office of Compensation and Working Conditions.

In BLS’ widely cited fatal occupational report released each year, deaths due to illnesses are excluded from the count unless the fatal illness is precipitated by an injury.

Because many illnesses take a long time to develop or be discovered, they are less likely than traumatic injuries to be documented on OSHA logs, Wiatrowski said, and employers likely use these logs to fill out their BLS survey forms.

Additionally, determining that an illness was triggered by workplace exposure sometimes can be difficult. Further complicating the issue are job turnover and retirement – how can an employer record an illness when the worker is no longer employed?

Currently, no plans are in place for the CFOI to report on occupational illnesses, or for the SOII to begin collecting information on occupational illnesses that could develop in the future, according to Wiatrowski. Noting the likely undercounting of occupational illnesses in official government statistics, Trout said that people wishing for a more accurate number of afflicted workers have to instead rely on estimates from academia.

Based on research papers and studies, NIOSH believes between 20,000 and 40,000people die every year from cancers attributable to the workplace. In comparison, the CFOI from BLS reported 4,690 fatal injuries in 2010.

The general public “would be very shocked” to learn the number of deaths caused by occupational illnesses, said Celeste Monforton, a professional lecturer at the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health at George Washington University. “This is the untold story,” she said.

Identification

Receiving an accurate count of how many employees become ill or die each year due to workplace exposures is only one difficult aspect of the occupational health field. As Trout put it, officials would rather prevent these illnesses than count them.

But even identifying these illnesses for prevention can be difficult because, at least at first, illnesses are less recognizable than injuries. “It’s really difficult to hide an amputation or a burn because it’s a physical manifestation of the hazard. It’s very apparent,” Monforton said.

Illnesses, however, do not have that immediate manifestation. Because some occupational illnesses develop over the span of years, occupational health professionals are not fully aware of the health outcome from exposure to many different chemical agents.

Complicating matters is diagnosis. Many general clinicians do not fully appreciate the potential role occupational exposures have in the cause of illnesses, Trout said, as doctors do not receive enough training to recognize the connection. From a clinical physician standpoint, the end process – which is the disease – is the same whether the illness was caused by occupational exposure or through some other means.

“Illnesses are harder to recognize as occupational-related [than] injuries,” Trout said. “The end process is someone has asthma. You could link it to occupational exposure in some cases, but of course lots of people have asthma that isn’t related to occupational exposure.”

Furthermore, for any given cancer, it is difficult to say what type of exposure caused it; instead, cancers are “strongly associated” with various occupations. However, a few exceptions exist, such as asbestos- or vinyl chloride-caused cancers, Trout said.

Monitoring

Eric Frumin, health and safety director with Washington-based union coalition Change to Win, stressed that the difficulty of linking exposures to cancers with great certainty is only true in individual cases. Once individual cases are put together, Frumin said, recognition can link those cases to a common exposure. “In the aggregate, there is no mystery,” he said.

Such a collective recognition of diseases makes monitoring important – a lesson NIOSH learned from the aftermaths of Hurricane Katrina and 9/11. Following the 2010 Deepwater Horizon explosion and oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the agency launched an unprecedented project for monitoring the health of the thousands of workers cleaning up the waters and the coast.

Some OSHA standards also have medical monitoring requirements, although these efforts are limited. “A challenge from OSHA’s vantage point is that they regulate active workers,” said James Frederick, assistant director of health, safety and environment for the Pittsburgh-based United Steelworkers.

When people change jobs or retire, they are no longer being monitored, despite possibly experiencing continued effects from an exposure. Frederick said it is not OSHA’s responsibility to continue monitoring former workers; the medical system as a whole must take it up.

Agency action

OSHA has had success in the past in drastically reducing the risk of some occupational health hazards. One of the agency’s greatest success stories – OSHA administrator David Michaels has repeatedly referred to it when confronted by critics wishing to stall new regulations – is that of OSHA’s actions against vinyl chloride.In the early 1970s, a rash of diagnoses of a rare liver cancer among workers at a Kentucky vinyl chloride plant was linked to the chemical. OSHA issued an emergency standard; a final standard limiting exposure followed a year later. In contrast to warnings from companies that the standard could ruin the industry, manufacturers found that the standard saved lives – and money.

Other examples of OSHA interventions include crackdowns on asbestos and, more recently, how industries have changed food-flavoring formulas after the butter-flavoring chemical diacetyl was linked to a lung disease commonly referred to as “popcorn workers lung.”

“Once the recognition is there, it doesn’t matter how long for the next case, the question is, ‘Are we going to do something about it?’” Frumin said.

One way to do something about the issue is to update permissible exposure limits. Many OSHA PELs are considered out of date, as they have not been updated since originally being instituted in the early years of the agency, despite advancements in research and better understanding of exposure effects.

Although many advocates of stronger regulations would like to see updates to these standards, Monforton points out that PELs – no matter how low – are not foolproof protection against occupational illnesses.

“There has never been an OSHA standard that has established a safe level of exposure,” she said.

For example, a PEL of 2 milligrams per million cubic meters of air for a substance may result in an excess of 20 lung cancers a year, whereas a PEL of 1 milligram may still have 10. But if the lowest feasible level small companies can achieve is a PEL of 5 milligrams, then that is the lowest level OSHA can enact in a standard.

Despite this apparent handicap, Monforton stressed that enacting a standard to the lowest possible level is not necessarily the goal. “What the level is is really less important than the recognition that workers are exposed and that there are feasible ways to reduce that risk,” she said.

Employer and employee steps

Employers could follow recommended exposure limits from NIOSH, in addition to PELs. “We feel they are an important part of preventing exposures and minimizing health effects,” Trout said of RELs.

However, just as OSHA does not have PELs for every chemical agent or substance, some agents have no RELs. In those cases, NIOSH recommends minimizing exposure and using the best available information.

Employers wishing to protect their workers from the risk of occupational illnesses can take proactive steps such as following RELs or voluntary consensus standards, and educating their workforce about possible health hazards associated with their duties.

“There is a general understanding in this country that toxic chemicals can do very bad things to people in the form of occupational illness and disease,” Frumin said. “If you don’t have a business model which commits the company, management and supervisors to evaluate the health and safety of their workers, you’re not going to achieve the protection you need to stop something like occupational diseases.”

Frumin recommended employees try to find out as much information as they can about their work environment and the materials they handle to educate themselves. With this information – which may include RELs, risks of exposures or mitigation techniques – workers can help get their employers to protect them.

John Franklin, whose silicosis brings chest pains with any exertion and leaves him easily winded, wishes he had spent more time checking out the information on Material Safety Data Sheets and taking precautions to protect his health.

“Just do some research and find out what this stuff is you’re working with, what it can do, and wear appropriate safety gear,” he recommended. “If you don’t feel like gearing up or sweating too much, you need to find another job.”

*Name changed to protect from possible repercussions.

The politics of occupational health

A major stumbling block in protecting workers from occupational illnesses and diseases is the crumbling political discourse, according to some stakeholders.

Although Republicans often have been blamed for impeding occupational health protections, delays in promulgating new standards are not strictly limited to partisanship.

Calling current OSHA administrator David Michaels a “luminary” in the occupational health field, Celeste Monforton said the trained epidemiologist’s agenda has been hindered by resistance from the Obama administration. That resistance, she said, is a result of the political climate seen today when regulations are viewed by some people as barriers to job creation and economic growth.

“The evidence of harm to workers from work exposures is there, but we see an Obama administration that is quite timid to talk about controlling these hazards so the harm is prevented,” said Monforton, a professional lecturer at the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health at George Washington University. “That’s really an unfortunate consequence of the very damaging anti-regulatory rhetoric.”

One example is a prolonged delay in the development of an updated silica standard. Given the devastating effect the compound can have on workers, many stakeholders insist a stronger permissible exposure limit is necessary. The current standard is decades old and includes PELs based on research that is even older.

When Safety+Health went to press, a proposed rule updating OSHA’s silica standard had been under review by the White House’s Office of Management and Budget since Feb. 14, 2011. A review typically takes 90 days.

Some stakeholders have suggested the delay will continue into at least November due to politics.

“This bickering back and forth … that is really what is holding back any progress in any area,” said a foundry worker suffering from silicosis caused by nearly two decades of silica dust exposure who asked not to be named. “That’s not the way a government is supposed to work. It’s supposed to come to a solution.”

– KWM

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)