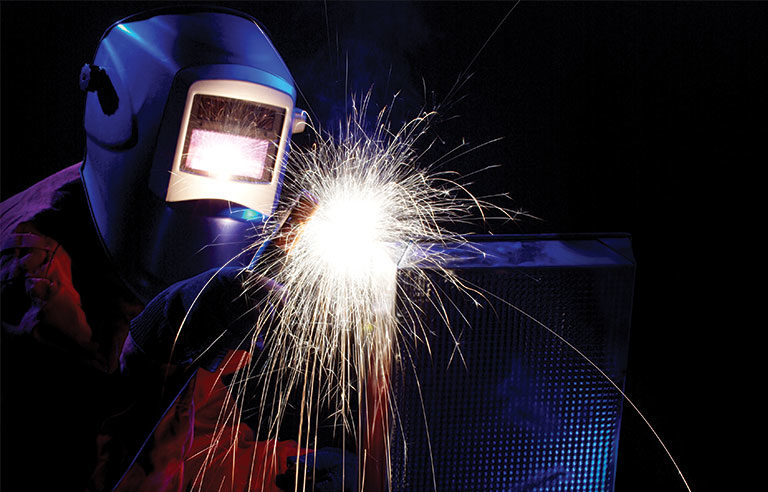

Hot work hazards

Taking proper precautions is vital to avoiding injury, death

The fire began in the afternoon on March 26, 2014, at a four-story brownstone in Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood, not far from the Charles River. It grew into a nine-alarm blaze that ultimately took the lives of 33-year-old firefighter Michael Kennedy and 43-year-old Lt. Edward Walsh. It also injured 18 other people, including 13 firefighters.

OSHA investigators determined that the fire was caused by welding sparks propelled by strong winds that ignited a shed. Workers – reportedly operating without a city permit – were attempting to install railings on a rear staircase at an adjacent building.

“OSHA found that the company (Malden, MA-based D & J Ironworks) lacked an effective fire prevention and protection program, failed to train its employees in fire safety, did not have a fire watch present, and did not move the railing to another location where welding could be performed safely,” Brenda Gordon, the agency’s area director for Boston and southeastern Massachusetts, said in a September 2014 press release.

Welding is a form of “hot work,” a term covering any activity that produces flames, sparks and/or heat. The wide-ranging definition includes not only obvious tasks such as welding, cutting and grinding, but also soldering, brazing, drilling (which can create heat from friction) and even thawing pipes.

Preventing incidents

Although hot work presents a number of risks, the potential for starting a fire is among the most significant. That’s why asking whether hot work is necessary and looking for alternatives are the initial recommendations from organizations such as the National Fire Protection Association and the Chemical Safety Board.

NFPA’s 51B Standard for Fire Prevention During Welding, Cutting and Other Hot Work was published in 1962, predating OSHA by nearly a decade. OSHA used that standard to craft part of its general requirements on Welding, Cutting, and Brazing (1910.252), and refers users to NFPA 51B “for elaboration.”

In the NFPA standard, the next step for safe hot work is to try to perform activities in a “designated area,” defined as “a specific location designed and approved for hot work operations that is maintained fire-safe” and “that is of noncombustible or fire-resistive construction, essentially free of combustible and flammable contents, and suitably segregated from adjacent areas.”

If hot work can’t be performed in the designated area, the next step toward safety is a detailed and thorough hazard assessment. Many organizations manage this with the use of a hot work permit.

“The permitting process, if it’s been properly drawn up, will include pre-work hazard assessment,” said Tim Healey, retired director of safety at the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Co. in Connecticut. “People have to have specific, detailed knowledge of the worksite. They have to have an understanding of the nature of the work that is envisioned, whether they’re burning, cutting, welding or brazing. It takes a purposefully executed job safety or job hazard assessment process.”

That process is especially vital when a job includes people from the outside, such as contractors, who may not be as familiar with a worksite. One of the most significant parts of the hazard assessment is looking for any potential flammable or combustible materials, even subtle ones.

Controlling fuel sources

By the nature of hot work, avoiding two parts of the “fire triangle” – oxygen and heat – virtually is impossible. Therefore, safety professionals and workers need to focus on controlling the third part of the triangle: potential fuel sources, said Guy Colonna, division director of technical services at NFPA. The 51B Standard recommends moving any possible combustible or flammable materials at least 35 feet away from the hot work area.

If they can’t be moved outside that zone, shielding materials such as welding blankets, curtains or pads must be used. The ANSI/FM 4950 Standard details the requirements of these items.

The 35-foot threshold can increase, depending on the worksite’s environment and conditions. It also is prudent to notice any changing conditions during all phases of hot work.

For example, Colonna said, if a 35-foot boundary was set at 6 a.m. and the winds start to gust a few hours later in the middle of a job, then “none of the safeguards put in place are going to stay effective.”

He added: “One of the more common observations I see is that there tends to be a complacency that goes on and people fail to identify changes of conditions.”

Colonna said the “fire watch” – one of at least three individuals who can form an effective team for safe hot work – is best tasked with monitoring those changing conditions and stopping work if needed.

The most obvious of the three people is the “hot work operator,” whose focus on job performance could keep him or her unaware of an altered environment. The other member of the trio is the person in charge of approving the hot work, known in the NFPA standard as the “permit authorizing individual.”

A fire watch is required “when hot work is performed in a location where other than a minor fire might develop,” according to the 51B Standard.

The fire watch also should be used when:

- Combustible materials are inside the 35-foot radius, or if they are outside the 35-foot boundary but there’s a chance they could be “easily ignited” by sparks

- Hot work residue might travel through openings in a wall or floor – within the 35-foot radius – and travel into a nearby area, such as concealed spaces

- Materials are present that are “likely to be” ignited on the other side of a ceiling, roof, partition or wall

The fire watch is trained to look for embers, sparks or anything else that may cause a fire. If a fire begins, he or she must attempt to extinguish it or alert someone.

The fire watch is required to stay vigilant for at least 30 minutes after work is completed, but that could change to 60 minutes when NFPA makes its next revision to the 51B Standard, which is expected to become available electronically in the fall of 2018.

More than one fire watch may be required if the hot work is taking place at an elevated level. A second fire watch would look for embers or residue that could ignite down below.

The consequences

Failure to take proper precautions can prove catastrophic. Hot work incidents logged by CSB in the past 17 years have resulted in 24 deaths.

Two recent investigations conducted by CSB involved the same company, Packaging Corp. of America. The most recent occurred in February at a plant in DeRidder, LA, where a welding operation caused an explosion that killed three contractors and injured seven others. A hot work explosion also took place in July 2008 at a PCA facility in Tomahawk, WI, resulting in three fatalities.

In 2010, CSB released a video, “Dangers of Hot Work,” and issued a safety bulletin that included a set of recommendations. Foremost among those was the use of combustible gas detectors before and during hot work.

OSHA regulations state that hot work should not be performed “where flammable vapors or combustible materials exist,” but the agency doesn’t specifically require detectors. However, its Oil and Gas Well Drilling and Servicing eTool recommends using them.

NFPA’s 326 Standard for the Safeguarding of Tanks and Containers for Entry, Cleaning, or Repair requires that if “flammable vapors in the atmosphere exceed 10 percent of the lower flammable limit” that work must stop in or around a tank or container. The source of that vapor must then be found and controlled or eliminated.

The standard also recommends testing “before and during any hot work, cutting, welding or heating operations” when inside or near containers or tanks that have or once held flammable or combustible liquids or gas.

CSB pointed out that all 11 incidents highlighted in its 2010 safety bulletin involved work in or around tanks that contained flammable materials.

Training

In response to the 2014 fire, the city of Boston requires anyone seeking a hot work permit to undergo safety training, which began in September 2016. NFPA partnered with the Boston Fire Department on a curriculum, which as of July 2017 had instructed about 17,000 people.

“I think that [the feedback is] supportive from the standpoint that they don’t want to be the ones that cause a similar or repeat event,” Colonna said.

The program is a promising step toward better safety consciousness, said Steve Hedrick, manager of safety and health with the American Welding Society.

“[NFPA and the Boston Fire Department] came out with their hot work certification program, which mandates that people become educated and follow the procedures,” Hedrick said. “That’s an entirely appropriate step.”

The Massachusetts Department of Fire Services told Safety+Health that it will work with NFPA to offer the training program throughout the state. Colonna said NFPA has developed an online instructional module, which could help get the program to other areas.

The American Welding Society estimates that 370,000 welding jobs will become available over the next nine years and, with many of those potentially filled by newcomers to the industry, proper safety education could prove even more vital.

Healey said training for those new workers should be designed “in such a way that it becomes embedded in the natural way that they go about their work.”

Hedrick noted that AWS is doing its part by providing free copies of the ANSI Z49.1 Standard for Safety in Welding, Cutting and Allied Processes on its website.

“I think the problem is lack of awareness of the requirements and procedures to do [hot work] safely,” he said. “If a person is trained and they follow the procedures, then they shouldn’t have any problems.”

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)