The ROI of safety

What to consider when analyzing the economic benefits of safety

Safety professionals whose employers are reluctant to invest in occupational safety may face an additional challenge when building their case: multifaceted math.

Although calculating a return on investment in safety lacks a universal formula, many experts agree that the exercise is worth the effort to support an investment that yields positive results. “When improving safety for the merit of just having a safer workplace is not enough, it’s often a very powerful argument with leadership to help explain the cost of safety by showing the economic benefits of safety,” said Ken Kolosh, manager of statistics at the National Safety Council.

Here are a few strategies to consider when crunching the numbers.

Show your work

Knowing how much an injury costs is vital when determining the ROI of safety. It’s also a valuable tool for any safety professional seeking additional justification to support investments in safety.

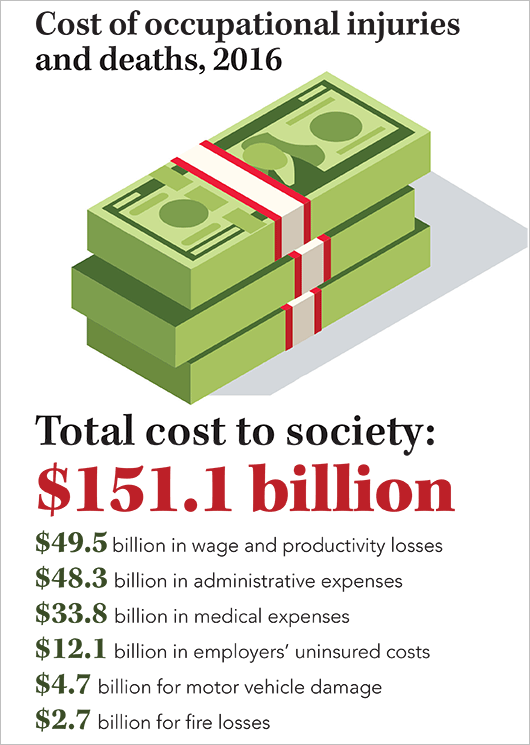

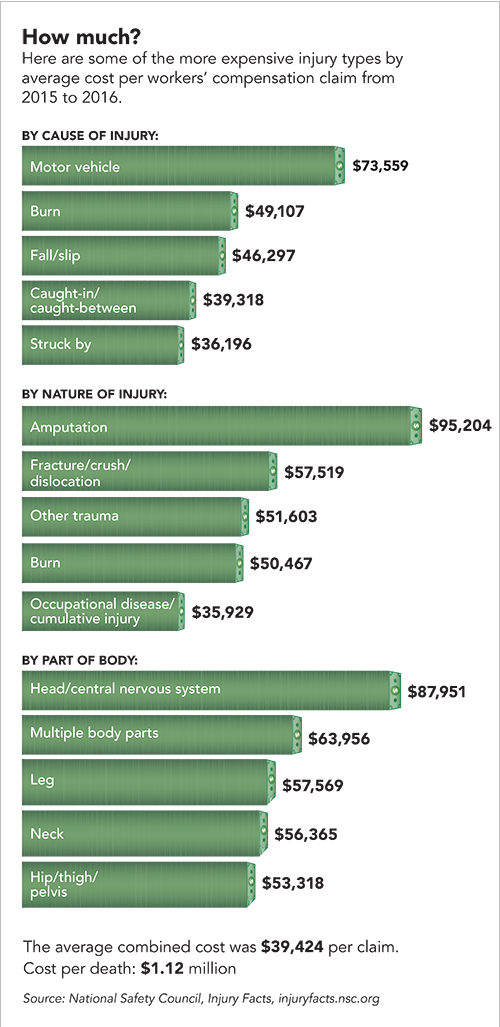

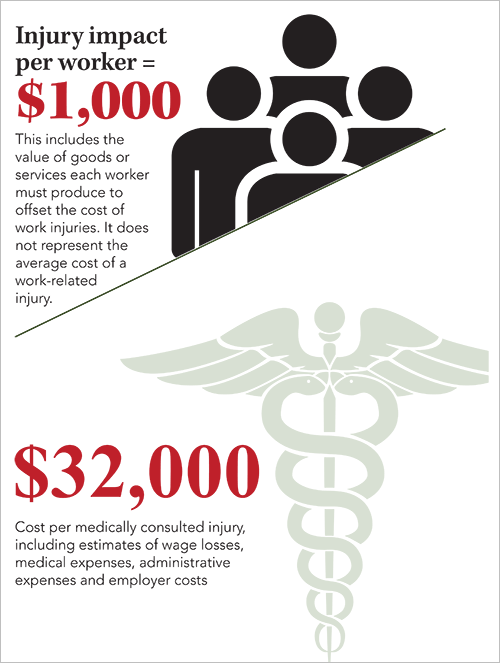

According to estimates from Injury Facts, an online statistical data resource developed and maintained by NSC, workplace injuries and deaths cost the U.S. economy $151.1 billion in 2016. That total accounts for numerous factors, including wage and productivity losses, medical expenses, administrative expenses, motor vehicle damage, employers’ uninsured costs, and fire losses. Injury Facts also states that the cost to society per medically consulted workplace injury in 2016 was $32,000. The cost per worker – not to be confused with the average cost of a workplace injury – was $1,000.

Experts such as Kolosh and Jim Spigener, chief client officer for Oxnard, CA-based consulting firm DEKRA Organizational Safety and Reliability, say that when employers perform estimations, they should consider both the direct and indirect costs of injuries. Direct costs include workers’ compensation and medical and legal costs. Examples of indirect costs include lost productivity, training replacement employees, incident investigation and implementation of corrective measures, and repairing damaged equipment and property.

The estimate of the total economic cost supplied by NSC is not the only one in circulation. Other organizations, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, use different models to estimate the costs of workplace injuries and fatalities, and those models may change over time. Some may reflect only direct costs.

For instance, although the 2016 NSC figure seemingly represents a notable drop from the $198.2 billion estimated cost of workplace injuries and deaths in 2012 – as outlined in the 2014 edition of Injury Facts – it’s important to note the council has since revised its estimating benchmarks and procedures. Kolosh and the subtexts of various Injury Facts charts and appendices are quick to warn that “cost estimates are not comparable from year to year.”

Selling safety

Not all organizations count on financial reasons as a driver for advancing safety, Kolosh said. For those that do, he suggests an internal benchmarking study as a sound starting strategy for making the business case for safety to a manager or employer.

The idea: Take three to five workplace injuries that typically occur in an organization and perform a “deep dive” analysis with colleagues from the purchasing and accounting divisions to determine each individual cost associated with the injury. Spare no expense to quantify all related figures.

“If it’s truly important to your organization, it’s probably worth making the investment of ascertaining the exact costs that are incurred when an injury occurs within their organization,” Kolosh said. “And then once that internal benchmark is determined, they can then use that going forward to provide much more accurate cost estimates to their leaders – and much more believable, because it is data that has been generated internally and it reflects their own organization.”

Presenting this information to leaders can help clear a path to cost savings for the organization through avenues such as lower workers’ compensation and medical costs and avoiding OSHA penalties.

“There are some companies that care about their employees. There are other companies that just care about the bottom line,” said Ted Miller, principal research scientist with the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation. “But it never hurts to be able to make the business case – and it’s also important to remember that, basically, the injury costs come out of your profits.”

Thinking critically

A 2007 study led by Oregon State University associate professor Anthony Veltri states that “many occupational safety specialists and academics have argued that occupational safety is good for business; however, the rationale is based on anecdotal evidence and opinion surveys.” The authors set out to gather empirical data, and affirmed that safety indeed was “good for business” upon monitoring work practices at 19 manufacturing firms.

Ron Gantt, director of innovation and operations for Reflect Consulting Group, also believes in finding specifics. Gantt stresses the importance of critical thinking when determining the ROI of safety and its many variables and challenges, beginning with defining precisely what “safety” means.

“If we define safety as things that we don’t want to have happen, we actually, I think sometimes in making our business case to people … create conflict,” Gantt said. “Because all of a sudden, we position ourselves as part of the organization that is designed to hold the organization back. And I think we would actually be more effective if we reframed the argument toward defining safety as what we want, right?

“So, what are the things that safety should create, not just what are the things that it should prevent? Yeah, we certainly want the prevention side, but if that’s all we ever talk about … we’re a bunch of Debbie Downers, you know? So maybe we need to start talking about what it is we actually want to create in the organization. How can we use the tools of safety to actually help create that?”

As an example, Gantt recommends thinking of a risk assessment not as a means to identify what could go wrong, but instead as a way to “figure out how we can keep [an operation] doing what it’s supposed to do.”

Safety+Health's editorial team interviews DEKRA consultant Jim Spigener about the ROI of safety in the May 2021 episode of the magazine's “On the Safe Side” podcast.

When analyzing the cost efficiency of specific safety and health interventions – such as training programs, new equipment or risk assessments – focus on what you’re aiming to accomplish, how it will be measured and what would constitute success.

“Then you can report back to management that you are demonstrating results, or (say), ‘Hey, we tried something with good intentions but it didn’t work, and now I’m getting rid of it,’” Gantt said. “You seem like a more reasonable person when you do that than if you just say, ‘Well, it’s in the name of safety, we’re going to do it.’”

Successful measures

Miller offered several anecdotal examples of proven, employer-driven safety and health interventions that can help reduce injury risks and promote cost savings. They include:

- Substance abuse prevention programs

- Fall prevention training

- Motor vehicle safety initiatives, such as mandating seat belt use

- Lower back and lifting ergonomics. “Anybody who’s lifting can lift more safely if they’ve been properly trained or briefed,” Miller said.

- Respirator use for workers in hazardous chemical situations

- Lockout/tagout

Various studies reflect correlations between proactively investing in occupational safety and health and experiencing lower incident rates and higher profit margins.

In February 2018, the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine published an economic analysis of 19 randomized, employer-driven interventions outlined in studies from 2005 to 2016. Results showed that 11 were cost-effective. Of the interventions identified as not cost-effective, a majority focused on individual – not organizational – levels, the authors wrote.

In 2014, a study from the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work found that small and medium-sized organizations may experience a positive ROI in safety investments within five years.

Making safety investments applicable to entire organizations should be the aim, experts note. A successful end result can pay dividends at all levels.

“Investing in safety is also investing in operational and behavioral reliability,” Spigener said. “Companies that demonstrate strong organizational support for safety experience improvement not only in safety, but also in absenteeism, employee turnover and other indicators of employee well-being.”

Miller shares that sentiment while emphasizing the need for employer awareness of proper safety protocol.

“I think that it’s important for the leadership to make sure that their safety people are listened to, and that there’s an environment that recognizes that safety is an important part of good business,” Miller said, “even if it slows work down a little bit at times … because then you don’t have incidents. Overall, you get more done at the end of the week.”

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)