NFPA 70E: A look at the 2018 edition

The updated standard highlights hazard elimination and human performance, and adds an arc flash PPE table

Electricity surrounds us and sustains much in our daily lives, yet it remains a hazard in the workplace.

The National Fire Protection Agency’s standard for electrical workplace safety, NFPA 70E, undergoes updates every three years in an effort to keep employers and workers safely in compliance with OSHA 1910 Subpart S and OSHA 1926 Subpart K. The standard aims to reduce on-the-job exposure to shock, arc flash and arc blast. The 2018 edition of NFPA 70E went into effect in August.

According to the 2017 edition of “Injury Facts,” an online statistical data resource from the National Safety Council, exposure to electricity resulted in 154 workplace fatalities and 1,850 cases with days away from work in 2014.

“Electrical injuries don’t happen very often, but when they do happen, they have a very high potential to be fatal,” said Lanny Floyd, former consultant for electrical safety and technology at DuPont Engineering. “One in 13 lost time injuries from electrical energy is fatal.”

Here, Safety+Health presents an overview of some key elements of NFPA 70E 2018.

Hierarchy of Controls

The revised NFPA 70E prominently highlights the Hierarchy of Controls within the standard, emphasizing the acts of risk identification and mitigation before the job begins.

Starting with the most effective controls and proceeding to the least effective, the hierarchy, as defined by NIOSH, flows as follows: elimination, substitution, engineering controls, administrative controls and personal protective equipment.

In total, NFPA 70E 2018 references the hierarchy 17 times, including five times in specific requirements, said Daniel Roberts, a Mississauga, Ontario-based senior manager of electrical safety consulting for energy management specialist Schneider Electric. Those figures were four and two, respectively, in the 2015 edition, Roberts said.

“Emphasizing the Hierarchy of Risk Control methods steers the electrical professional away from a PPE risk-reduction response to consider a more effective and reliable risk-reduction method, or combination of methods,” Roberts said.

Floyd said the top three control measures are more effective given their focus on facility design, citing an example in the construction industry as a potentially efficient application. According to a study from the Center for Construction Research and Training – also known as CPWR – 82 construction workers were electrocuted in 2015, accounting for 61 percent of all work-related electrocutions that year.

Because construction workers often face exposure to overhead power lines, Floyd suggests reassessing construction site planning methods before beginning work. Employers should consider the location of the receiving area for accepting electrical materials. They also should be mindful of the routes trucks, cranes, forklifts or other vehicles will take, as well as additional ways to eliminate exposure to risk areas.

“Too often, the question is not being asked: What can we do to reduce the risk of electrical hazards at a work facility?” Floyd said, adding that the continued emphasis on the Hierarchy of Controls creates a potential for synergy among industry workers.

“The safety professional brings a wealth of knowledge in risk management and risk assessment and risk reduction that many electrical experts don’t have,” Floyd said. “And if we can engage in a meaningful collaboration between safety pros and electrical experts, there may be many opportunities to refine the electrical safety program in all aspects, from design solutions to safe work practices to selection of PPE, etc.”

New arc flash PPE table

During an arc flash event, an electric current leaves its intended path – either traveling to the ground or passing by air from one conductor to another. Arc flash temperatures can reach 35,000° F – roughly three times hotter than the surface of the sun.

Relocated from Annex H, a new arc flash PPE table, “Table 130.5(G) Selection of Arc-Rated Clothing and Other PPE When the Incident Energy Analysis Method is Used,” provides a quick reference guide in NFPA 70E 2018.

For incident energy exposures of 1.2 cal/cm2 to 12 cal/cm2, the standard requires the use of hard hats, hearing protection and leather footwear, as well as one item from each of these groups:

- Long-sleeved shirt and pants, coverall, or arc flash suit

- Arc-rated face shield, arc-rated balaclava or arc flash suit hood

- Heavy-duty leather gloves, arc-rated gloves or rubber-insulating gloves with leather protectors

- Safety glasses or safety goggles

Arc-rated outerwear – such as jackets, parkas, rainwear and hard hat liners – can be used as needed.

Incident energy exposures of 12 cal/cm2 or greater require the use of an arc-rated flash suit hood, hard hat, hearing protection and leather footwear. Workers also must select one item from the following groups:

- Long-sleeved shirt and pants, coverall, or arc flash suit

- Arc-rated gloves or rubber-insulating gloves with leather protectors

- Safety glasses or safety goggles

Arc-rated outerwear can be worn as needed.

The table also stipulates that employers are not required to provide workers with arc flash protection for exposures below 1.2 cal/cm2 because “the expected injury from an incident will be survivable and nonpermanent.”

Still, Hugh Hoagland, senior managing partner of Louisville, KY-based e-Hazard, an electrical safety training and testing provider, advises employees in such situations to wear non-melting clothing if any chance of an arc flash event exists. Hoagland doesn’t recommend working in polyester clothing.

“Assess the circumstance, see if you think there’s any likelihood of occurrence or enough energy that it would cause clothing ignition,” Hoagland said during a Nov. 30 S+H webcast covering 70E changes affecting PPE.

Accounting for human performance

Annex Q introduces the idea of human performance and explores tools to address human error. Roberts attends 70E meetings as part of his role in maintaining Canada’s corresponding standard on electrical safety in the workplace and said the material is a copy of an annex found in the 2015 version of the Canadian standard, CSA Z462.

“The basic principle of human performance is that humans are fallible – even the best-intentioned person errs,” the annex states. “The objective of human performance is to identify and address human error and its negative consequences on people, programs, processes, work environment, equipment or an organization.”

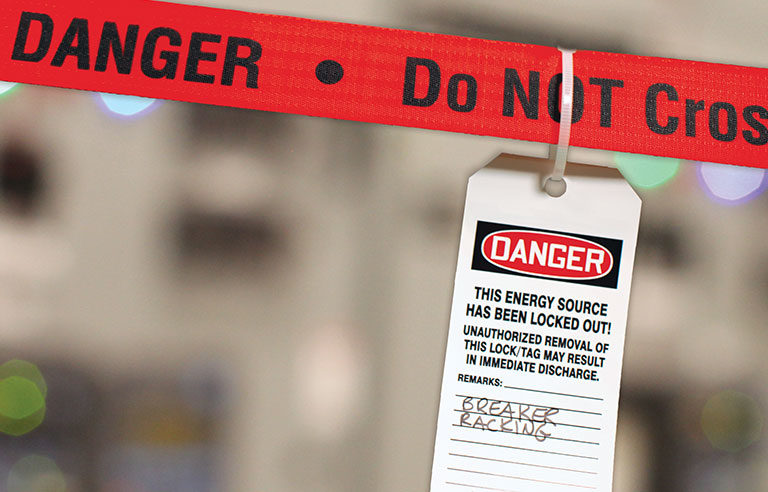

However, several past editions of 70E have featured requirements considered human error-reduction techniques. For example, Roberts said, a technique known as flagging and blocking is evident in Section 130.7(F), stating that employers should enact one or more alerting techniques to prevent employees working on de-energized electrical equipment from accessing energized electrical equipment in the same area.

Other human performance tools include pre-job briefing, jobsite review, post-job review, procedure use and adherence, self-check with verbalization, three-way communication, and stop when unsure.

“Safety professionals should be careful not to confuse human performance theory and tools with the behavior-based safety approach,” Roberts said. “Behavior-based safety, when applied at the worker level, generally seeks to modify what’s going on between the worker’s ears to reduce error (i.e., pay attention).”

He continued: “Human performance theory, when applied at the worker level, seeks to modify the workspace, workflow and work procedures to reduce error, or the effects of error.”

Added Hoagland during the webinar: “You definitely want to think about it so that PPE doesn’t become the source of a new error.”

Moving forward

The NFPA 70E committee invites feedback throughout each standard cycle. Roberts recommends visiting www.nfpa.org to share thoughts electronically.

“Any changes to the standard result from public input,” Roberts said. “So, you might have a great idea, you go to the NFPA website, you submit your idea through their public input portal and then the technical input committee considers it. … So, it’s an open and transparent process to change the standard. What would be really nice is if more safety professionals got involved. To date, it’s mostly the electrical professional.”

As the author of various accepted changes to the standard throughout his career, Floyd finds a forward-thinking approach to be beneficial.

“You can’t just be focused on what’s in the standard,” he said. “Somebody has to be looking ahead and looking at who’s doing the things that may appear radical today but one day will be the norm.”

Popular articles from the Safety+Health archives

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)