2013 State of Safety

Following record lows in 2009, the rates and numbers of both fatal and nonfatal injuries and illnesses have flattened, leaving safety and health professionals to wonder what may occur if the economy continues its slow grind toward recovery.

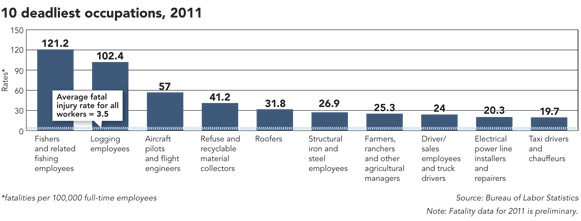

In a series of reports issued this past fall, the Bureau of Labor Statistics detailed some of the changes – or lack thereof – in occupational injury, illness and fatality data between 2011 and previous years. For the first time in a decade, instead of declining, the incidence rate of injuries and illnesses remained unchanged – 3.5 cases per 100 full-time workers for both 2010 and 2011. (Data for 2011 is the latest available.)

Bureau of Labor Statisics reports:

The number of fatalities per 100,000 workers slightly declined between 2010 and 2011 – from 3.6 to 3.5 – returning the rate to its 2009 level. However, the 2011 fatality data is preliminary, and final 2011 figures – expected this spring – could raise the rate back to 3.6.

Since the Great Recession ended, unemployment (one indicator of the economy’s strength) has dropped from 9.1 percent in January 2011 to 7.7 in November 2012, according to the latest data available at press time. The effect the improving economy has had on occupational safety and health is, at the moment, a mystery.

“Given the ongoing economic improvements, it’s likely employment will further increase [into 2013], and the question is will that further strengthening of the employment situation be detrimental to safety,” said Ken Kolosh, manager of statistics at the National Safety Council. “We just don’t know.”

Exploring the possibilities

The national trend of steady rates is being experienced by individual employers. In Santa Clarita, CA, Tami Royer works as the safety coordinator for utility provider Castaic Lake Water Agency. Over the past two years, CLWA’s injury rates have flattened out, and Royer said others in her industry and related industries, such as the chemical industry, have experienced similar patterns.

Royer said CLWA employees – who contend with potentially serious hazards such as various chemicals – still experience injuries, but those injuries are minor in nature. “In one respect, it makes me feel good because we’re not having the major types of injuries that we could,” she said. “But the fact we have minor injuries tells me we need to keep tweaking.”

In the event that the economy continues to improve, occupational safety may be affected in a few different ways. Kolosh noted that prior to the recession, the stronger economy did not appear to have a negative effect on safety: injuries and fatalities declined. However, in a typical recovery, occupational injuries and deaths increase as new employees join the workforce.

“The conventional wisdom is when you get a growth in the economy, you get an influx of people behind the learning curve,” said Jim Spigener, senior vice president at BST, an Ojai, CA-based consulting firm. These people include inexperienced workers and those who may have formerly been in the workforce but are returning to either new positions or old positions with changed technology, putting them at a disadvantage that could result in injuries.

If the economy were to grow rapidly, an uptick in injuries could occur, according to Spigener. But if growth is slow – which appears to be the case – keeping a larger workforce safe would be “very manageable,” he said.

But Spigener pointed out that he is not convinced of a link between the current economy and the plateau in injury and illness data. Many industries – particularly those related to oil – are starting back up with a number of inexperienced workers, and more safety professionals and upper management are striving for the goal of zero injuries or fatalities, he noted. These two events balance one another out and lead to national occupational data remaining flat, according to Spigener.

“I think there’s a fairly significant movement in the safety world to not accept anything less than zero, and I think that’s genuine,” he said.

Changing the message

Not every employer will be in a position to see declining injury numbers and rates, Spigener said, noting that some safety programs may be out of reach for small businesses.

At Castaic Lake Water Agency, Royer’s safety budget was not cut during the recession – but it did not increase either. This has helped her maintain the status quo of low injury rates and zero serious injuries or fatalities, but has prevented her from pursuing methods to eliminate hazards that still cause minor injuries.

During the recession, Royer was asked to stretch the safety dollar further than in the past, including shortening the length of training time and looking into cheaper equipment – options she does not agree with.

“The problem is production is about money, and money is about production, and safety isn’t a priority at first,” Royer said.

In his years as a safety professional, Mike Clark has learned safety can become a priority for employers, but not necessarily always for altruistic reasons.

“They start to see it impact their bottom line, and that’s what triggers it,” he said.

Clark has worked for three different companies in an environmental, health and safety position during the past 12 years, and currently is the safety manager at AgFeed USA in Ames, IA. The international agribusiness remained unaffected by the recession, but the company’s growth and high workers’ compensation costs prompted management to hire Clark as its first dedicated safety specialist. With its newly established safety and health program, direct compensation costs were expected to lower by about $4 million in 2012 from 2011, Clark said.

Safety professionals’ mindsets have had to change following the recession, Clark claims. Before, he said, selling management on safety may have focused solely on the positives of keeping people safe, but it has now changed to a message of protecting the employer from unexpected losses.

“We’re still getting from point A to point D, but B and C are different,” Clark said about keeping people safe. “The way we’re getting there is different.”

New data

One thing that may help employers and safety professionals get from point A to point D is more detailed data. With the release of its latest reports on occupational safety and health, BLS is using a revised coding structure in its manual for its Occupational Injury and Illness Classification System. As a result, data about the nature of injuries is more detailed.

“For getting into the weeds, there’s going to be a lot more information and better information,” Kolosh said.

For example, previous BLS data on fatal falls noted whether the fall was to a lower level from stairs, a ladder or a roof. The new data details the height of the fall in a range of feet – less than 6 feet, 6-10 feet, 11-15 feet and so forth.

For Royer, the new data will be very helpful – she likes to look at the national data to see the “what ifs” occurring in her industry. “It helps you plan how you’re going to approach safety,” she said. “The more specific you are, the more you can focus in your training on things that are an issue.”

Along those lines, the more detailed data also could help safety professionals in their pitches to upper management, Spigener suggested. For instance, knowing an increasing number of older workers are dying from ladder falls could help a safety manager convince an executive to invest in a different system.

“Being able to look at that kind of data helps you make the case you shouldn’t be doing X or you shouldn’t be doing Y,” he said. “You’re going to see the ability to discern and make those kinds of choices.”

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)